Omani Princess Salmah (Emily Ruete ) was born in 1844 on Zanzibar and the daughter of Said bin Sultan, Sultan of Oman and Zanzibar.

She was the first Arab woman to write an autobiography (1886), with many interesting details about her life in Zanzibar the Omani palace.

Emily eloped from Zanzibar and married a German (Heinrich Ruete) and lived many years in Germany. In her works she also compares living as a woman in Zanzibar and Germany. Her memoirs were first published in German in 1886 and in 1888 in English.

May 2017 an article by Hielke van der Wijk about Emily Ruete and her works was published in the annual of the Dutch Bibliophile Society (Jaarboek van het Nederlands genootschap van Bibliofielen (pages 183-205) This article contains detailed information and many illustrations of the different early editions of her "Memoiren 1886" / "Memoirs 1888" Emily's work has been republished many times in recent decades and in several languages.

In this website we refer at many places to passages in her very interesting book. So her book is also highly important for understanding the use of antique Omani / Zanzibari objects.

Oscar Wilde read her memoirs and wrote in the magazine Woman's World : “The story of her life is as instructive as history

and as fascinating as fiction"

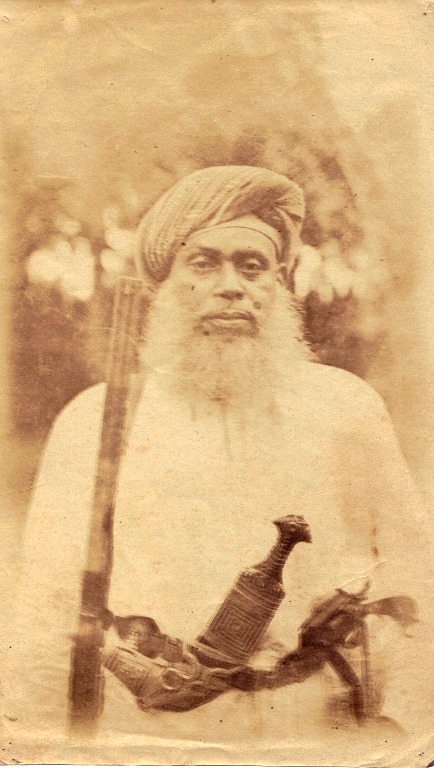

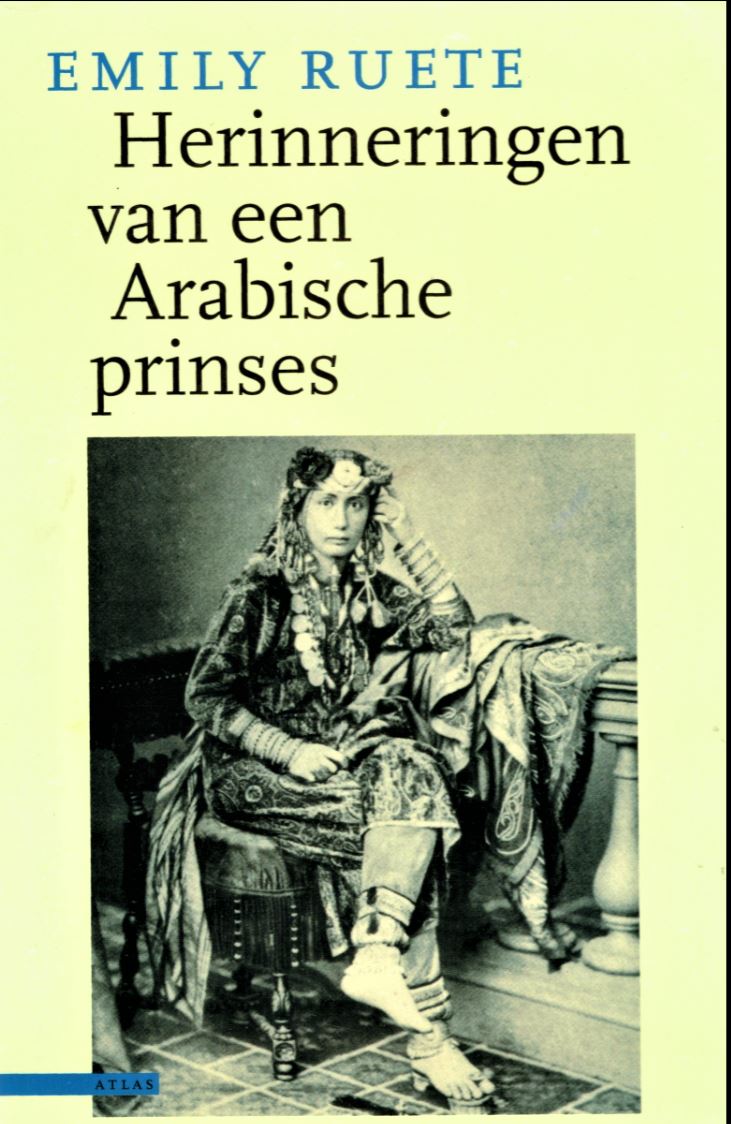

Princess Emily Ruete in her Omani costume. The photo was the only illustration in her memoirs. The large majority of newspaper critics were very positive about her memoirs except the Berlin correspondent of the English Times who wrote: "Princess Salme who gives a frontispiece presentment of herself in the barbaric glory of her native costume and also suggested the book was not written by her etc. "

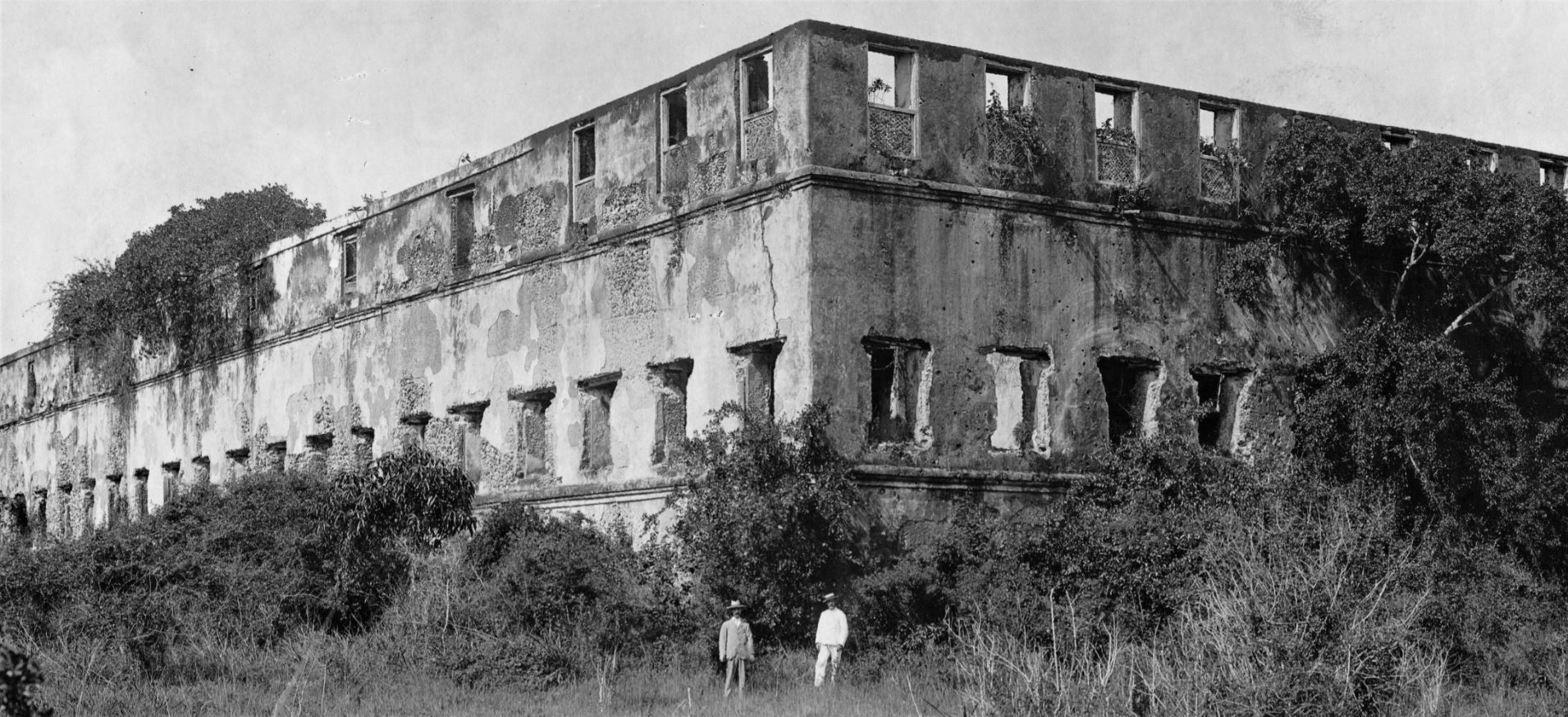

Emily was born as Princess Bibi Salme / Salmah in 1844. She grew up in the enormous Mtoni palace beautifully located outside Zanzibar Town next to a stream and the sea. Over a thousand people were living in this palace. Richard Burton who lived on Zanzibar compared the palace with a Gothic castle of a German prince!

Emily Ruete was born in Bet il Mtoni Palace in 1844 (Photo from around 1900 shows the ruins of the palace)

She learned herself to write by copying the Holy Koran. Her father died in 1856 and then the Sultanate was split after two of her brothers could not agree who to become the new Sultan. Oman was run by her half-brother Thuwaini and her other half-brother Majid run Zanzibar. Majid suffered from the unknown disease epilepsy, many locals believed his illness was caused by evil spirits (Jinns)! Because Emily's father died, she became automatically of age, despite being only 12 years old and inherited a large sum of money and a plantation.

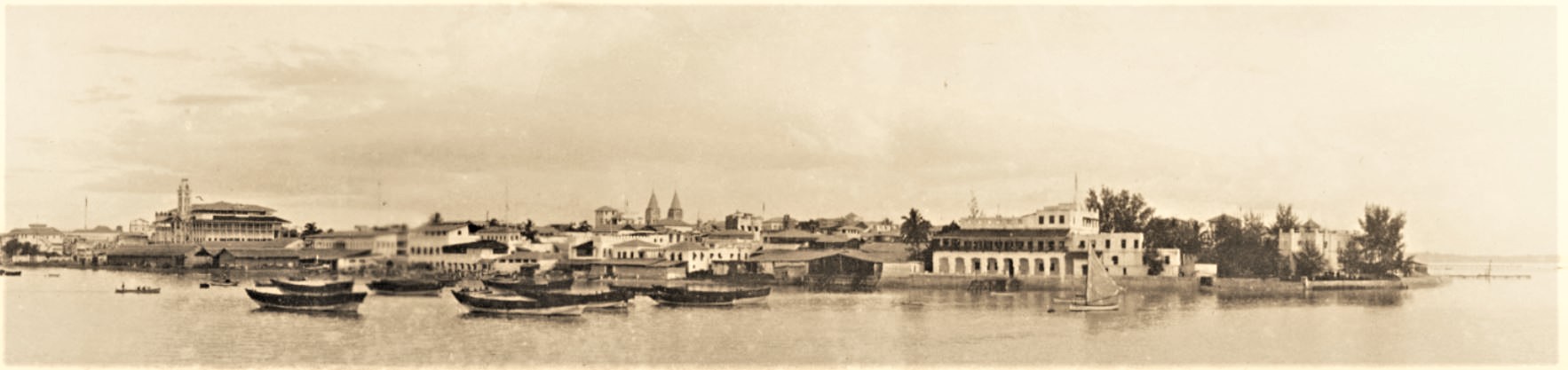

Zanzibar Stone-town around 1900

In 1859 Salme's brother Barghash started a coup against Sultan Majid. Salme, 15 years old, got involved, partly because she was able to write confidential letters. The coup failed because action was taken by the British and subsequently Barghash was deported to Bombay. After some time Majid re-established family contact with Salme but many family members ignored her because of her role in the coup against Majid. As a result Salme was more and more drawn towards the Europeans on the island.

When Emily met Heinrich she lived in the house top right, photo probably taken by John Kirk around 1870 (part of a rooftop panorama probably taken from the clock-tower) According to van Donzel (page 14 Plate VII), based on a photo with manuscript inscription from son Rudolph, Emily lived in the part of the house with 4 lower windows that is painted white. The upper storey was supposedly added later when the Hansing firm acquired the house.

In 1865 she met the German trader Heinrich Ruete, fell in love and got pregnant. When she discovered Sultan Majid wanted to execute her, she escaped from the Island with help of the British to Aden. After 6 months she converted to Christianity, married Heinrich and departed for Germany. From now on her name was Emily Ruete. In Hamburg she was happy and gave birth to three children: Antonie, Rudolph and Rosalie. In 1870 disaster struck and Heinrich was killed by a horse-tram. Emily, only 25 years old, did become a widow with three small children in a foreign country. To Emily's astonishment she and all women in Germany, were not allowed to manage their own finances..... Two male caretakers managed her finances and lost a large part of her capital. In Zanzibar Emily did run her own plantations and finances! Life became difficult for her financially with three children and she started to teach Arabic. The fact that a princess became a teacher even reached the Dutch newspapers:

April 7 1879 Arnhemsche Courant (also in two other Dutch papers)

(Several Dutch newspapers reported the news that a Royal (Emily) had to earn her living by becoming a teacher!)

Emily Ruete's brother Sultan Barghash 1875

In 1870 her brother Barghash became Sultan of Zanzibar. In 1871 the German empire was founded with an Emperor and Bismarck as a political leader. Bismarck raised at Emily's request the issue of her remaining inheritance with her brother Barghash, but without result. Emily made friends with the very influential Baroness van Tettau. She raised her problem with Victoria, daughter of Queen Victoria of Britain and who was married to the son of the German emperor. In 1875 Barghash came to London and Emily also went to London and tried to contact her brother. However the British government tried everything they could to keep Emily away from Barghash. The British royals tried to help Emily but the Sultan did not give in. When Barghash went to the horse-races at Ascot the Royals ignored him and he was not to allowed to join the Royal stand. In the end the British government promised financial compensation for Emily and she left the UK, but later the British did not full-fill their promises!

Barghash at Ascot, but not in the royal stand. Quite a few horses at the races may very well have been of Omani descent 1875

Because diplomacy did not work, Emily decided to get involved in the East African colonial politics of Germany. She wrote a secret letter in Arabic to her brother Barghash with the message that he should not trust the British, instead he should support the Germans and with her knowledge of the West she could help him how to best deal with the European colonial forces. Barghash did not respond and passed the letter to John Kirk the British Consul (see Kirk Papers)

In 1884 the (brutal) German adventurer Carl Peters came to the East African mainland and negotiated "contracts" with different (illiterate) tribal heads that gave his "Gesellschaft fur Deutsche kolonisation" (theoretically) complete power of these areas in exchange for protection (promises which he could not really meet) and some small presents.

Early 1885 the Berlin conference led by Bismarck took place, during which European colonial nations divided up most of Africa between them and agreed to abolish slavery. Bismarck saw a strategic opportunity for Germany in the "contracts" negotiated by Peters and German Emperor Wilhelm I agreed military protection for the area of the "Gesellschaft" which meant it formally became a German protectorate. Barghash totally disagreed with the German protectorate, because the Germans claimed territory, that was his!

Photo of the Zanzibar palaces and the clock-tower around 1885

Behind the lighthouse is located the House of Wonders. These buildings were bombed by the British fleet in 1896. When rebuilt , the tower and palace were integrated.

Meanwhile Emily and her children secretly travelled via Port Said to Zanzibar, for the first time in 19 years she would return to the island. The last stage she travelled as "secret cargo" on the freight ship Adler that, close to Zanzibar, was joined by a squadron of German warships. The warships were positioned opposite the Sultan's palace and the cannons were visible prepared for action. The British were at that time involved in several other military actions elsewhere in the world and did not want another conflict, so they persuaded the Sultan to accept the German protectorate. After this success the Germans raised the issue of the remaining inheritance of Emily, but the Sultan refused. The German admiral decided to let Emily go on shore, with German protection, where she was warmly greeted by the citizens of Zanzibar who walked along with her, this very much upset her brother Sultan Barghash. After a few days, Berlin told Emily to go on board and travel back to Germany. During her absence The German and British representatives tried to persuade the Sultan to pay Emily 6000 pounds but he was only prepared to pay 6000 rupees (500 pound) this was of course not acceptable to Emily.

In 1884 Emily had completed most of her memoirs and tried to get it published, however she could not agree on the financial terms with publisher Carl Hallberger.

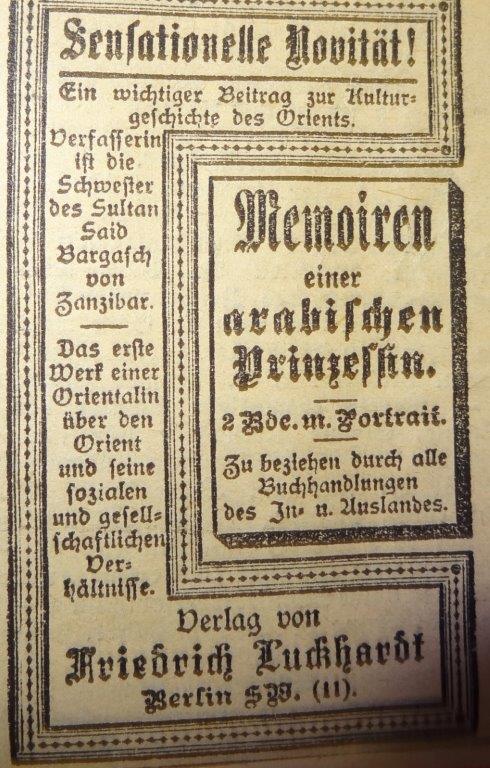

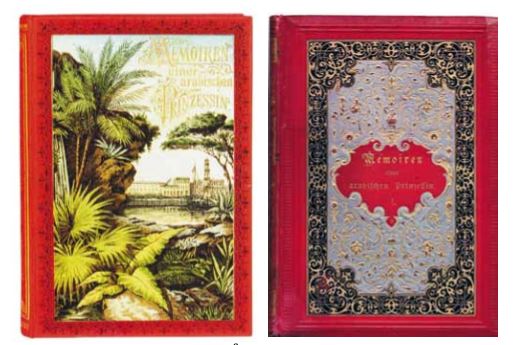

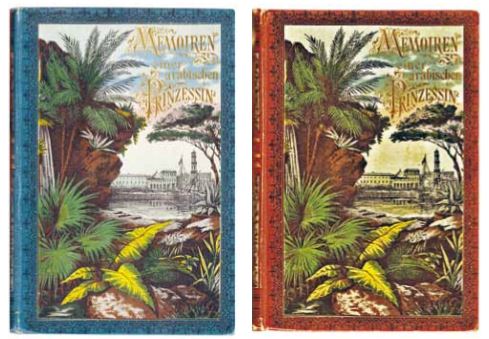

In 1886 her Memoirs finally came out, in German, with the title "Memoiren einer Arabischen prinzessin" publisher Friedrich Luckhardt . Emily had added an extra chapter to her book. The Memoirs contain a lively and colourful description of her life at the Zanzibar court from a cultural and political point of view. Emily felt that the Germans saw the East as a fairytale land, an image that was influenced by the Orientalism in art with their harems and fantasy buildings and also by the uncensored edition of Richard Burton's 1001 nights. Interesting are the contrasts in customs and culture she highlights between East and West including education, health, materialism, position of the Eastern Woman, Arab view on slavery. Also items such as wedding proceedings, Ramadhan, Eid , illness and influence of magic on daily life are discussed. Emily observed that in the free West many marriages are also unhappy and that arranged marriages can work if husband and wife have mutual understanding for each other. She also finely reminds that polygamy also exists in the West with the Mormons. In the East men are also reluctant to have multiple wife's as it can lead to jealousy and some women included in their marriage contract that their husband could not marry more wife's.

Emily says she wrote the book for her children, but she probably also intended to influence public opinion regarding the inheritance she claimed from her brother. Many positive reviews of the book were published in the German newspapers. The English newspaper the Times was more cynical (probably for political reasons). From May 1886 till October four editions of the German Memoiren were published, and then it ended.

The princess and her son Rudolph kept an album with newspaper cuttings with advertisements, articles and reviews of her book in 1886. The album also contains articles regarding the visit of Barghash to London. This album is part of the "Said Ruete Library" in Leiden University / NINO Holland.

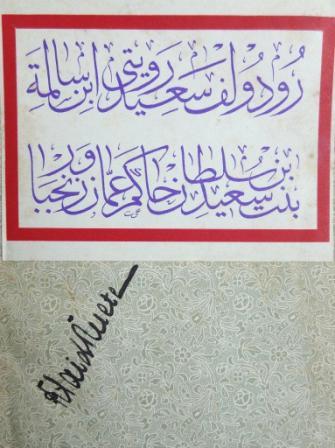

One example of the 1886 memoirs contains a dedication by Emily to her son Rudolph in Arabic:

"Peace, a greeting and thousand

love tokens from your mother

Salma bint Said Sultan"

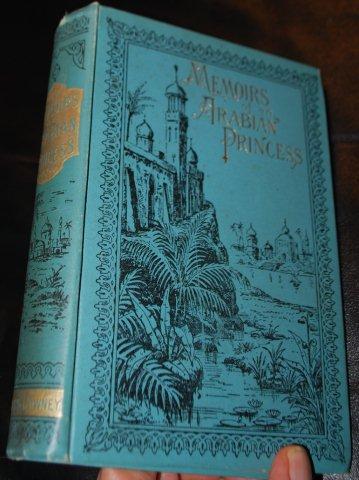

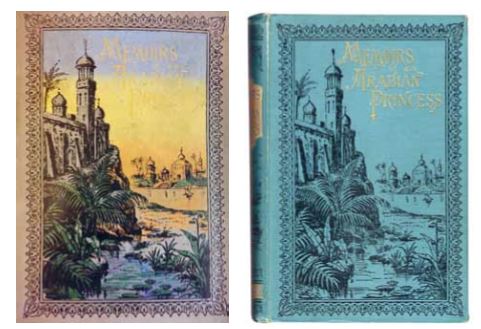

On January 5 1888 the first English edition named "Memoirs of an Arabian Princess" came out with publisher Ward & Downey in London. Some months later an American edition and a slightly smaller format and printed on cheap thin paper comes out with publisher Appleton, this was probably a pirate copy as there was no copyright in the US at that time.

This photo of Sultan Barghash (Emily's Brother) was taken during his visit to London 1879

The author Oscar Wilde writes a very positive review about her book in Woman’s World March 1888: „Her book throws a great deal of light on the question of the position of women in the East, and shows that much of what has been written on this subject is quite inaccurate. [...] No one who is interested in the social position of women in the East should fail to read these pleasantly-written memoirs. The Princess is herself a woman of high culture, and the story of her life is as instructive as history and as fascinating as fiction"

First English edition by Ward & Downey Jan 1888. Note: The cover does not depict the palaces at Zanzibar accurately (fantasy landscape). Ward & Downey published mostly novels.

Zanzibari Omani led by Buschiri started an uprising (Araberaufstand) in 1888 against the Germans and their own weak Sultan of Zanzibar, because their trade was being taken away by Carl Peter's "Gesellschaft". In the end the German navy had to help the "Gesellschaft" to end the uprising in 1890, this included a naval blockade of the East African coast. Bushiri was captured and subsequently hanged by the Germans. It was clear that the "Gesellschaft"could not manage the area on their own. From then on the "Gesellschaft" did effectively become the colony German East Africa.

Buschiri leader of the Arab uprising (Araberaufstand 1888-1890)

March 1888 Sultan Barghash died and he was succeeded by Sultan Khalifa, another brother of Emily. In April 1888 Emily went on her own initiative back to Zanzibar with daughter Rosalie, they arrived in May. She asked the German consul to sent her letter to Sultan Khalifa but he refused. Subsequently she cursed everything German! She asked the English consul if she could get British citizenship but this was not possible. In the end she probably got some money from ladies in the palace and decided not to return to Germany. instead she moved very disillusioned to Jaffa and in 1892 she moved to Beirut. Finally in 1914 (because WW1 was imminent) she returned to Germany where she died in Jena 1924 and was buried at the cemetery of Ohlsdorf near Hamburg.

Book-plate & signature of Rudolph Said-Ruete son of Emily Ruete. The calligraphic text reads:

بنت سعيد بن سلطان حاكم عمان وزنجبار

رودولف سعيد روتي ابن سالمة

Rūdūlf Saʿīd Rūtī ibn Sālima

bint Saʿīd bin Sulṭān ḥākim ʿUmān wa-Zanjabār

Rudolph Said Ruete, son of Salma

bint Said Sultan, ruler of Oman and Zanzibar

The calligraphic Ex-Libris is copied from a manuscript document probably given by the Sultan of Oman in 1932 when Rudolph got the title Seyyid and was recognised as a member of the Sultan's family (the manuscript is currently owned by Rudolph's grandson Michael Bauer)

Carl Peters was in 1893 recalled from East Africa because of his brutal behaviour against the local black population and died in 1918, but was rehabilitated by Hitler in the 1930's.

In 1894 Rudolph Said-Ruete worked for a year at the German imperial consulate in Beirut, the city were Emily was living then. Rudolph Said_Ruete was a German army officer but resigned from the army in 1898. In 1901 Rudolph married Maria Theresa Matthias, her mother was the daughter of an important German-British family of Industrialists (founder ICI), named Mond. From 1906 till 1910 Rudolph was director of the important Deutsche Orientbank in Cairo, during this period he became quite wealthy. He was involved in large infrastructure transactions including railway investments. In 1914 Rudolph lived in London, just before the first world-war in July he moved to Switzerland escaping imprisonment by the British as he was a German and former army officer. In the UK Rudolph's capital was frozen. In Germany some people saw him as a traitor, probably including his brother in law General Troemer.

Around 1920, after the war, Rudolph returned to London. With the rise of the German Nazi party in Germany he resigned his German citizenship and became British and continued living in London. In 1932 Sultan Khalifa of Zanzibar bestowed the title "Sayyid" upon Rudolph Said-Ruete. This made him an official member of the Al Bu Said family. During the 1920's Rudolph tried to mediate, as an independent negotiator, between the Jews and Arabs in Palestine and made several constructive proposals and corresponded with people like Chaim Weizmann. Through the years Emily, Rosalie and Rudolph corresponded with their friend the Dutch Arabist Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje. who was the founder and head of the "Oosters Instituut" in Leiden Netherlands.

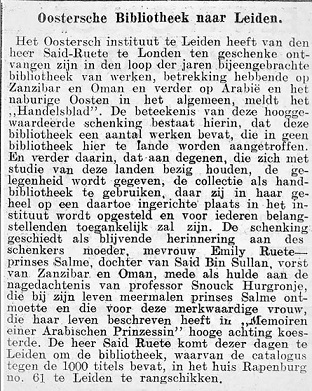

In 1885 Snouck first met Emily at a lecture he gave in Germany about his stay in Mekka 1884-1885, the next time Snouck came to Germany he personally went to visit Emily. Snouck died in June 1936. In remembrance of their long friendship, Emily's children Rudolph, Anthony and Rosalie left in 1937 a collection of 800 books, manuscripts, photo's, paintings and some other items from their mother Emily and themselves to the "Oosters Instituut" in Leiden Netherlands. Most books came from Rudolph who complemented the books with thousands of newspaper article cuttings and many letters mostly relating to East Africa and Oman. This collection is called the "Said Ruete library"

Dutch Newspaper article from 1937, regarding the donation of the Said Ruete Library to the Oosters Instituut in Leiden:

In 1993 the head of the "Oosters Instituut" Prof. Dr. E. van Donzel wrote an excellent scientific edition of Emily's published and unpublished work, largely based on the fast information in the Said Ruete library. The book is named "Sayyida Salme / Emily Ruete An Arabian Princess Between two worlds" published by Brill Leiden. The Staatsbibliotek of Berlin has a permanent on-line exhibition about the life and works of Emily Ruete on their website. In the Palace Museum Bait al Sahel in Zanzibar is a room dedicated to Emily Ruete. In 1937 the official Zanzibar museum got a number of objects that belonged to Princess Emily from her daughter Mrs Antonie Brandeis-Ruete. these objects included a dress of velvet, a gold embroidered mask, a pair of silk trousers, a silk girdle an envelope for holding a holy Koran and a gold signet ring , bearing in Arabic the name of the princess. There is also an interesting private museum dedicated to Emily Ruete, part of the material is based on an earlier exhibition in Hamburg.

Strangely enough there has not yet been an Emily Ruete exhibition in the Netherlands, while for 80 years most information on Emily Ruete is to be found in Leiden!!

First detailed bibliography by Hielke van der Wijk of the early editions of Emily Ruete's Memoiren, in Jaarboek van het Nederlands Genootschap van Bibliofielen 2016

Four different covers of the first German edition issues of the Memoiren 1886

Issues of the genuine first English edition of the Memoirs 1888 by ward & Downey

Issues of the first American edition (most probably a pirate copy by Appleton 1888 (text is identical to the earlier Ward & Downey edition)

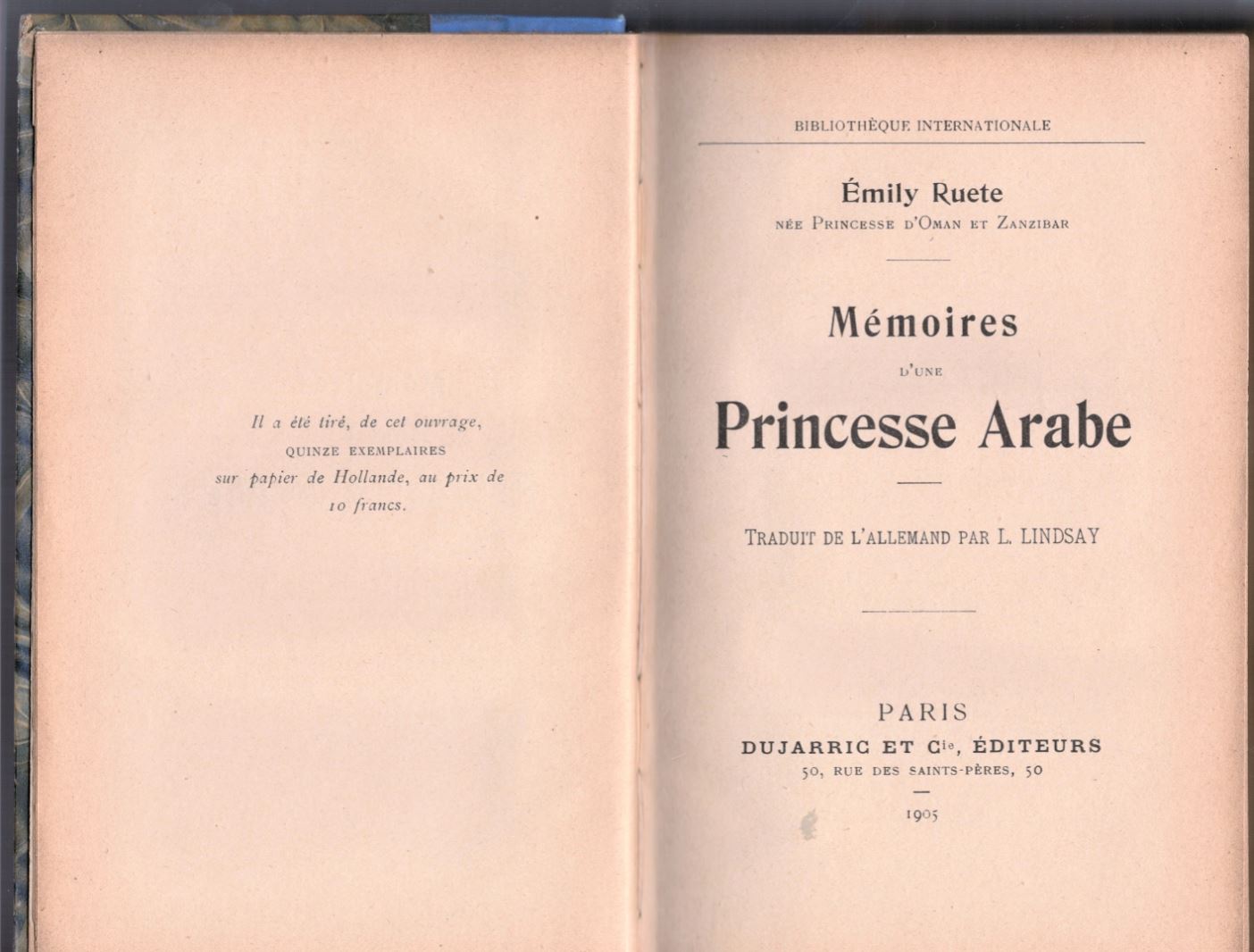

First French edition of the Memoires 1905

First Illustrated edition of the memoires in 1907(with revised English Text)

In 1985 the Memoirs were first published in Arabic with the title "Muḏakkirāt Amīra ʿarabiyya"; Qaysī, ʿAbd al-Maǧīd Ḥasīb al-; Masqaṭ : Wizārat al-Turāṯ al-Qawmī wa-al-Ṯaqāfa 1406/1985. This translation is based on the above American edition of 1907. Note that the English in that American edition deviates form the First English edition (Ward & Downey 1888). We also do not know how accurate / complete the Arab translation of the 1907 American edition is (see below). However we understand that some parts have not been included. On the internet was the following additional information (but we unfortunately lost the location / link and unfortunately cannot confirm it's accuracy): "The first Arabic translation of this autobiography was undertaken by Oman’s Ministry of Heritage and Culture in the early 1980’s and this dispels the general perception held at the time, that the Sultanate of Oman did not support its translation. This was of significant importance because it offered the Arabic reader the opportunity to acknowledge the book. This translation was based on one of the English texts, which was unfortunately not an accurate translation of the original book. Amendments made include chapters being combined and passages being moved from their original location. Therefore, the authenticity of the English and subsequent Arabic translated versions of the book are open to question. Moreover, the latter is further compounded due to the Arabic translator, Mr. Abdul Majid Hassib Al Quasi, distorting the text through omitting some parts altogether and adding his own personal embellished depictions. Consequently , the only authentic Arabic translation of the book is that of the Iraqi translator Dr. Salma Saleh, whose translation was based on original German text. This Arabic version of the autobiography was published twice in Germany by Dar Al Jammal in 2002 and later 2006"

First edition of the unpublished work in its original German 1997

Below you find detailed examples of the early editions of the Memoiren.